Who really put the Bible together?

Who put the Bible together? Despite what many assume, the Bible didn’t simply appear as a complete book. Throughout history, the compilation of sacred scripture involved numerous individuals, communities, and councils making critical decisions about which texts deserved canonical status.

Many people imagine the Bible as a single book handed down intact from ancient times. Actually, the formation of biblical canon represents a complex process spanning centuries. The Jewish scriptures underwent organization into the TANAK structure before the Septuagint translation expanded accessibility. Meanwhile, early Christians carefully evaluated texts based on specific criteria before accepting them as divinely inspired.

This article reveals the fascinating journey behind biblical canon formation, from the earliest Jewish collections through pivotal church councils. You’ll discover the four-part test applied to potential scriptural texts, learn why Catholic and Protestant Bibles contain different books, and understand how political and theological factors influenced what billions today consider God’s word.

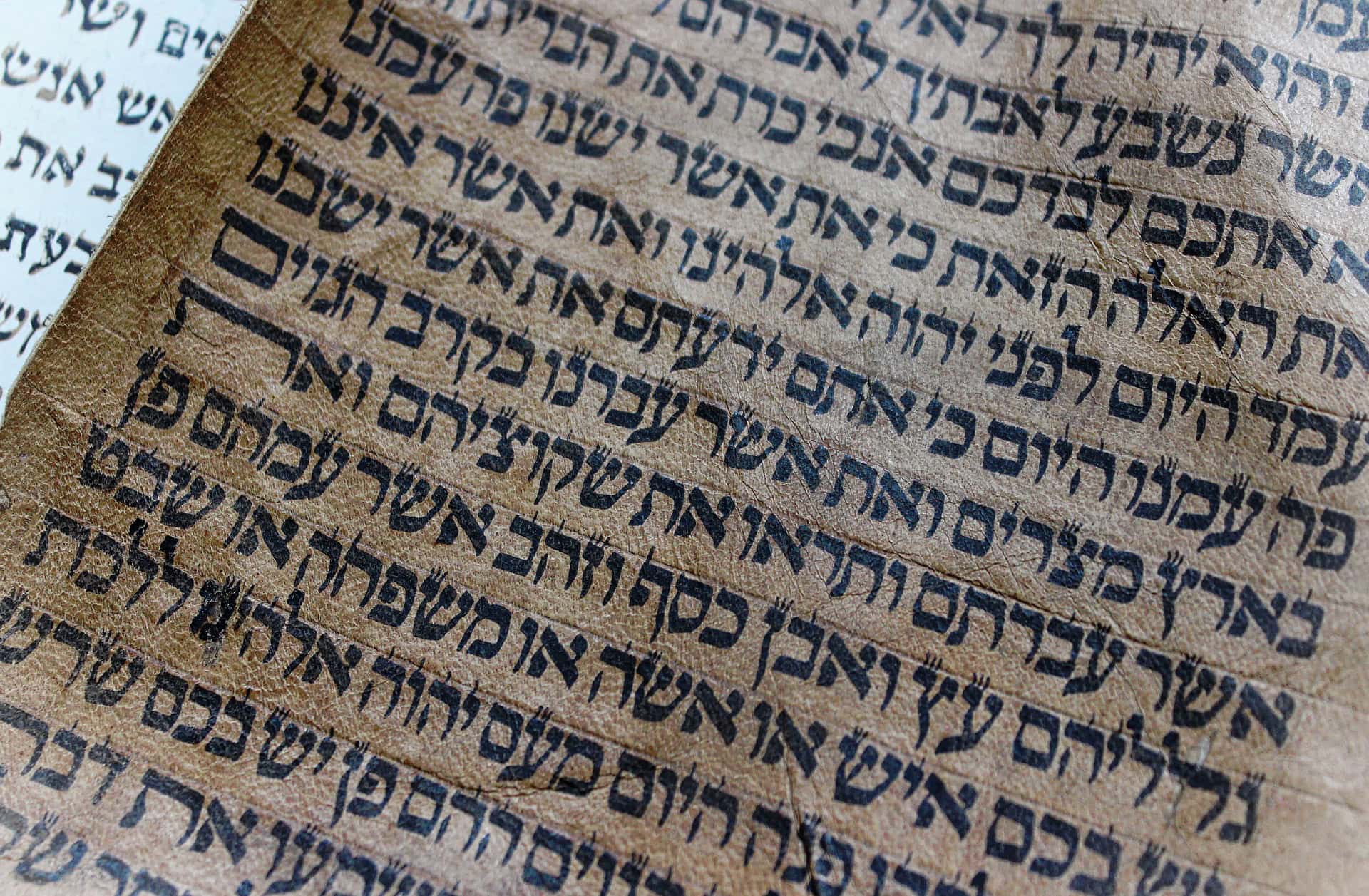

How the Jewish Scriptures and the Septuagint Translations developed?

The foundation of what would later become the Christian Bible began with ancient Jewish texts. These scriptures, with their distinct organizational structure, underwent significant transformation when translated into Greek, ultimately affecting which texts early followers of Christ would embrace as sacred.

What is the Structure of the TANAK: Torah, Nevi’im, Ketuvim?

Jewish scriptures are traditionally known as the TANAK, an acronym formed from the first letters of its three major divisions. The first division, “TA,” represents Torah (Law or Teachings), which consists of five fundamental books: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. These texts form the core narrative of Jewish identity, from creation through the exodus from Egypt and the giving of the law.

The second division, “NA,” stands for Nevi’im (Prophets). This section contains eight books: Joshua, Judges, Samuel (combined 1 and 2), Kings (combined 1 and 2), Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the Book of the Twelve Prophets. This last book encompasses twelve shorter prophetic works from Hosea to Malachi, considered a single unit in Jewish tradition.

The final division, “K,” represents Ketuvim (Writings), which includes eleven diverse texts: Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ruth, Song of Solomon, Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah (counted as one), and Chronicles (combined 1 and 2). In total, the traditional Jewish canon consists of 24 books, though this count differs from later Christian numbering systems.

How the Greek Influence and the Septuagint’s 46 Books came to be?

During the period of Hellenistic influence (approximately 300 BC to 70 BC), Jewish scholars undertook the monumental task of translating their scriptures from Hebrew into Greek. This translation, known as the Septuagint (meaning “seventy” for its supposed seventy translators), expanded the collection significantly.

The Septuagint’s expansion came through two primary mechanisms. First, some books that appeared as single volumes in the Hebrew tradition were separated (like Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles). Second, and more significantly, seven additional books were incorporated: Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), and Baruch. These additions, along with expanded versions of Esther and Daniel, brought the total to 46 books.

These additional texts are often called “deuterocanonical” (second canon) or “Apocrypha” (hidden) works. Although accepted among many Greek-speaking Jews of the Diaspora, they weren’t universally embraced by all Jewish communities, particularly those in Palestine adhering strictly to Hebrew traditions.

Why the Septuagint Was Used by Early Christians?

Early Christians adopted the Septuagint as their primary scriptural source for several reasons. First, most early Christians were Greek-speaking and lacked knowledge of Hebrew. Furthermore, the early Christian movement spread primarily through Greek-speaking regions of the Roman Empire, making the Greek translation naturally preferable.

Evidence of the Septuagint’s influence appears throughout early Christian writings. The New Testament contains approximately 350 quotations from Old Testament texts, most aligning with the Septuagint’s Greek wording rather than the Hebrew original. References to deuterocanonical books also appear in early Christian literature.

For instance, St. Clement of Rome (Pope from 88-99 AD) cited the book of Wisdom in his letter to the Corinthians. The Didache, containing apostolic teachings, referenced passages from Sirach. Similarly, St. Polycarp, Bishop of Smyrna (69-155 AD), quoted from Tobit in his letter to the Philippians written around 135 AD.

This widespread use established precedent for the Catholic Church’s later official acceptance of the fuller 46-book Old Testament canon, rather than reverting to the shorter Hebrew collection. Additionally, the Septuagint provided theological vocabulary and concepts that greatly facilitated early Christian interpretations of Jesus as the promised Messiah.

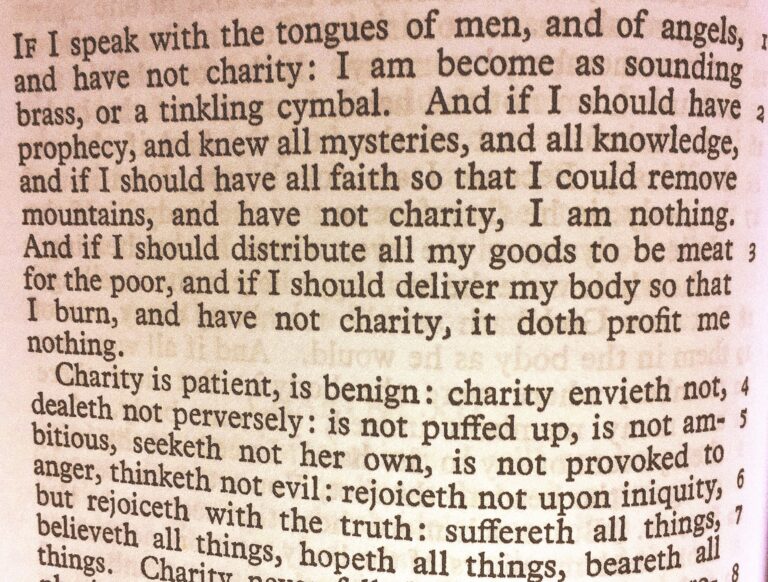

How the New Testament Canon Was Formed?

The formation of the New Testament as we know it today unfolded over several centuries through a careful process of discernment and evaluation. Unlike the Old Testament that existed before Christianity, the New Testament developed organically as the early Church sought to preserve authentic apostolic teaching.

A) Apostolic Authorship and Early Church Usage

The writings that eventually formed the New Testament originated in the first century, penned by the Apostles themselves or their close associates. While Jesus left no written texts, his followers recognized the need to document his life, teachings, and the growth of the early Church. Initially, these texts circulated independently among Christian communities, with some gaining widespread acceptance immediately.

The Catholic Church, as the only existing Christian authority during the first three to four centuries, became the custodian of these sacred writings. As the Pope and bishops received these texts, they assumed responsibility for determining which books truly contained divinely inspired teaching. This process wasn’t arbitrary but involved careful evaluation of each text’s origin, content, and reception among believers.

B) Rejection of Gnostic and Spurious Writings

Not every text claiming apostolic origins met the Church’s standards for inclusion in the biblical canon. Numerous writings emerged in the second and third centuries falsely attributing authorship to apostles while promoting teachings inconsistent with established Christian doctrine. The Gospel of Thomas serves as a prime example—though it claimed connection to the apostle Thomas, it contained Gnostic heresies that contradicted orthodox teaching, resulting in its rejection.

To systematically evaluate potential scriptural texts, Church leaders developed four crucial criteria:

- Antiquity: Did the text originate in the first century when the Apostles lived?

- Apostolicity: Was it written by an Apostle or someone closely connected to an Apostle (such as Mark’s connection to Peter or Luke’s to Paul)?

- Catholicity: Had the text received universal recognition throughout the entire Church?

- Orthodoxy: Did its contents align with the oral traditions preserved by Catholic bishops?

This methodical approach led to the final selection of 27 books that now constitute the New Testament, including the four Gospels, Acts of the Apostles, Pauline and Catholic Epistles, and Revelation.

C) The Role of Oral Tradition in Early Christianity

Notably, the New Testament canon emerged from a community that initially relied on oral tradition rather than written documents. Before texts were widely circulated, the teachings of Christ spread through verbal instruction. Consequently, when evaluating written works, Church authorities compared them against established oral teachings preserved by apostolic succession.

This oral foundation explains why “Orthodoxy”—consistency with traditional Church teaching—served as a key criterion. Books contradicting what had been passed down verbally through bishops were rejected, even if they claimed apostolic authorship.

The final recognition of the 27-book New Testament canon took shape formally in the fourth century, with Pope Damasus I in 382 AD issuing the first official decree concerning the biblical canon. Subsequently, the Councils of Hippo (393) and Carthage (397, 419) confirmed these selections, establishing the New Testament collection that Christians still use today.

How the Four Criteria were used to Finalize the Canon of the Bible?

Determining which texts belonged in sacred scripture required systematic evaluation criteria. The early Catholic Church, faced with numerous writings claiming divine inspiration, developed four specific standards to identify truly canonical works. These benchmarks formed the foundation for what would become the 27-book New Testament.

I) Antiquity: First-Century Origin Requirement

The first criterion concerned the text’s age. For a book or epistle to merit consideration, it needed to originate during the first century AD—the apostolic era when eyewitnesses to Christ’s ministry still lived. This temporal restriction ensured texts were written close to the events they described rather than centuries later. Books composed after this period faced immediate rejection regardless of other qualities. This chronological boundary served as an initial filter, eliminating many later writings that emerged during the second and third centuries.

II) Apostolicity: Connection to an Apostle

The second criterion required direct connection to an apostle. To qualify, texts needed to be either written by an apostle himself or by someone closely associated with an apostle. For instance, the Gospel of Mark gained acceptance because of Mark’s connection to Peter, likewise Luke’s Gospel through his association with Paul. This standard ensured the content reflected authentic apostolic teaching rather than later interpretations. The requirement maintained a chain of reliable transmission from Christ’s original disciples to the written texts.

III) Catholicity: Universal Acceptance in the Church

The third standard examined how widely a text had been embraced. To gain canonical status, a writing needed recognition throughout the entire Catholic Church across diverse geographic regions. Local acceptance proved insufficient—universal acknowledgment was necessary. This criterion protected against regional biases and ensured only texts with widespread acceptance throughout Christian communities entered the canon. This “consensus of the faithful” approach acknowledged the Holy Spirit’s guidance of the entire Church.

IV) Orthodoxy: Consistency with Church Teaching

The fourth criterion focused on doctrinal consistency. Texts contradicting established oral traditions preserved by Catholic bishops faced rejection regardless of claimed authorship. Indeed, several works claiming apostolic authorship were excluded specifically for doctrinal discrepancies. The Gospel of Thomas provides a classic example—though purportedly written by the apostle Thomas, it contained Gnostic heresies incompatible with orthodox teaching. Consequently, Church authorities rejected it despite its claimed apostolic connection.

Through this systematic four-part evaluation, Church authorities gradually identified which writings truly deserved canonical status. Pope Damasus I officially recognized this process in 382 AD, with subsequent councils at Hippo and Carthage confirming these selections. This methodical approach ultimately produced the New Testament collection Christians still use today.

How the Church Councils and Papal Decrees Finalized the Bible Canon?

The formal establishment of biblical canon occurred through a series of official church declarations spanning over a millennium. These authoritative pronouncements transformed what had been widespread but informal usage into binding religious doctrine.

A) Pope Damasus I and the Latin Vulgate

The foundational work of canonizing scripture began under Pope Damasus I in the fourth century. In 382 AD, he issued the first official papal decree on biblical canon, formally recognizing both the expanded 46-book Old Testament from the Septuagint tradition and the 27 books of the New Testament. This action provided the first authoritative statement on which texts constituted sacred scripture.

Moreover, Pope Damasus I commissioned a monumental translation project that would profoundly shape Western Christianity for centuries. He requested that Saint Jerome translate the entire Bible from its original Greek and Hebrew sources into Latin, resulting in what became known as the Latin Vulgate. This translation served as the Catholic Church’s standard biblical text for over a thousand years.

B) Council of Hippo (393) and Carthage (397, 419)

Following Pope Damasus I’s decree, several important North African church councils further solidified the biblical canon. The Council of Hippo in 393 AD affirmed the same canonical list established by Damasus. Shortly thereafter, the Council of Carthage in 397 AD reconfirmed this canon, with another Council of Carthage in 419 AD providing additional endorsement.

These councils proved pivotal in establishing universal consensus around the Church’s official biblical texts. Correspondingly, they strengthened the authority of the Septuagint tradition that included the deuterocanonical books which many Jewish communities had excluded from their Hebrew canon.

C) Council of Trent (1546) and the Deuterocanonical Books

After nearly a millennium of stable consensus, the Protestant Reformation triggered renewed debate about biblical canon. Martin Luther’s rejection of seven Old Testament books prompted a definitive Catholic response. On April 8, 1546, the Council of Trent issued an official decree reaffirming the complete 73-book canon (46 Old Testament + 27 New Testament books) that had been recognized since Pope Damasus I.

The Council specifically declared the deuterocanonical books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, and Baruch) as fully canonical, rejecting Luther’s relegation of these texts to secondary status. This decision ensured that the Catholic biblical tradition, first formally recognized in the fourth century, would continue unchanged despite Protestant challenges.

For this reason, the full 46-book Old Testament canon remains standard in Catholic Bibles today, a direct continuation of the tradition established by early church authorities nearly 1,700 years ago.

Why Protestant and Catholic Bibles Differ?

One of the most visible differences between Catholic and Protestant traditions involves their Bibles—specifically, which books they consider divinely inspired. This divergence, emerging during the Protestant Reformation, continues to distinguish these Christian denominations today.

Martin Luther’s Rejection of the Deuterocanonical Books

The 16th century marked a pivotal shift in biblical canon when Martin Luther challenged the long-established collection of sacred texts. Luther removed seven complete books from the Old Testament that had been part of Christian scripture for over 1,200 years. These texts—Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus (also called Sirach), and Baruch—became known among Protestant circles as the “Apocrypha” (hidden) and in Catholic tradition as “Deuterocanonical” (second canon) books.

Comparison of 39 vs 46 Old Testament Books

The fundamental difference between Protestant and Catholic Old Testaments comes down to these seven disputed books plus expanded versions of Esther and Daniel. The Protestant Bible’s 39 Old Testament books essentially match the expanded count of the Jewish TANAK structure: 5 books of Torah (Law), 21 books of Prophets (expanded from the original 8 by splitting combined books), and 13 writings. Conversely, the Catholic Bible contains 46 Old Testament books, maintaining continuity with the Septuagint tradition used by early Christians.

Impact of the Reformation on Biblical Canon

This canonical divergence prompted the Roman Catholic Church to issue a definitive response. On April 8, 1546, the Council of Trent officially declared the deuterocanonical books as fully part of the Christian Bible. This decree served as a direct countermeasure to Luther’s actions, cementing a division in Christian scripture that persists to this day.

Therefore, upon examining historical evidence, we find that the Catholic Bible’s 46-book Old Testament represents a continuation of the same canon officially recognized in the 4th century and used consistently for approximately 1,700 years. The Protestant 39-book Old Testament, in contrast, represents a 16th-century revision based on returning to the Jewish scriptural structure.

Conclusion

The journey of biblical canon formation, therefore, reveals a complex historical process spanning centuries rather than a single event. Initially, Jewish scriptures organized as the TANAK provided the foundation, while the Septuagint translation subsequently expanded accessibility and content. Early Christians adopted these texts alongside emerging apostolic writings that underwent rigorous evaluation based on four essential criteria: antiquity, apostolicity, catholicity, and orthodoxy.

Throughout this development, Church authorities played a decisive role in distinguishing authentic scripture from spurious texts. Pope Damasus I first officially recognized the complete 73-book canon in 382 AD, followed by confirmation at the Councils of Hippo and Carthage. This established tradition continued uninterrupted until the Protestant Reformation, when Martin Luther’s rejection of deuterocanonical books created the canonical difference that still distinguishes Catholic and Protestant Bibles today.

The Bible we know, accordingly, represents the culmination of careful discernment by numerous individuals and communities across different eras. Though many assume sacred scripture simply appeared as a complete work, its formation actually reflects a methodical process guided by specific standards and historical circumstances. This understanding deepens our appreciation of scripture not only as divine revelation but also as the product of a remarkable human journey through history, theology, and faith.